Albert George Swain

Private 9727 Albert George Swain, 2nd Battalion, Royal Berkshire Regiment

Albert was born in Newbury on 8 November 1896 (according to his school record) the eldest child of Francis Albert Swain and his wife Ada Ann née Emmens. His father, a house painter, died in early 1901 leaving Ada pregnant with their third child, Frances Emily, who arrived just in time to be recorded in the 1901 census (31 March) as 5 days old. The middle child was Alfred Mark, born in 1900, sadly he too died in 1901 shortly after the census was taken.

Raymond's Cottages ca1920, shortly before their conversion by Dr Essex Winter.. |

At the time of Francis’ death the family were living at 2 Lamb Cottages alongside the Lamb public house in Enborne Road. While Ada’s mother (Emma Emmens) moved in to help with the children it seems that they were unable to keep up with the rent; they moved to Raymond’s Cottages in Argyle Road. This was not high quality housing, in 1796 they were deemed inadequate for the use of the almspeople of the Raymond’s Almshouse Charity; the Church Almshouse Charity were less fussy and used the cottages until the 1880s when they too moved out to newly-built premises in Newtown Road. For the next 40 or so years they were rented privately to poorer families like the Swains. In the 1920s they were expanded and improved to create the current building, used by the Essex Winter Almshouse Trust. Ada found work as a ‘linen ironer’ working for a local laundry. Albert was educated in Newbury at St John’s Infants and St Nicolas’ National School; when he left school on 8 December 1910, he went to work as a grocer’s errand boy.

When war broke out in August 1914 Albert was still only 17, too young to serve overseas (army regulations clearly stated that soldiers should be 19 before they were sent into action). However, Albert had already enlisted into the 3rd Battalion of the Royal Berkshire Regiment, for a six year term in the Special Reserve (unlike Territorials Special Reservists could be called up and sent overseas). He signed up on 2 April 1914, telling the recruiting sergeant that he was 17 years and 115 days old (ie born 8 December 1986 – someone miscalculated or his school record was out by a month). He was 5ft 4 ½ ins tall, weighed 107bs and had blue eyes, dark brown hair and a scar over his right eye.

New recruits to the Special Reserve began by spending six months training, learning to be a soldier and gaining proficiency in the work of the unit they were in; in Albert’s case this would involve infantry skills. War broke out during Albert’s training so he would not have been ready for immediate posting to an active battalion (the 3rd Battalion remained in the UK throughout the war, primarily as a depot/training reserve). Nor was he sent out to France when the need for replacements was critical in October/November 1914 – perhaps the age regulations protected him at this point. However, despite their knowledge of his age, Albert was sent to abroad before he was 19; he landed in France on 10 June 1915. Many young lads went to France in 1914/1915, many because they lied about their ages, but there were also a good number of young pre-war recruits like Albert, many even younger than 18, whose desperation to go over with their mates or to get over and join the fight persuaded their regiments to turn a blind eye to the age regulations.

The regimental badge of the Berkshire Regiment, as used on CWGC headstones. |

The battalion was in trenches near Neuve Chapelle, the scene of heavy fighting in March but quiet by this date. The next few months saw the battalion splitting their time between trenches near Bois Grenier and rest billets at Fleurbaix; casualties were very light, sickness caused more losses than enemy action. This all changed on the evening of 24 September when the battalion went back into the trenches at Bois Grenier, but this time it would not be quiet - the battalion’s orders were to attack the enemy positions. The 2nd Royal Berkshires were a unit of the 8th Division, which was tasked with carrying out an attack to capture 1200 yards of the German front. This was not the main action of the day, that would take place around the village of Loos 15 miles to the south, it was one of a number of diversionary attacks designe dto keep the enemy guessing about the location of the main assault and hence prevent the transfer of reserves to Loos.

The battalion war diary entry gives few details:

War Diary, 25 September 1915 - 2nd Battalion, Royal Berkshire Regiment

The Battalion took part in an attack on the German position and during the day sustained the following casualties:-

Officers Killed: CAPTAIN R.W.L. OKE, CAPTAIN W.A. GUEST-WILLIAMS, LIEUTENANTS G.F. GREGORY, R.H.G. TROTTER, J. VESEY, R.H.L. SIMMONS and 2nd LIEUT B. RUSSELL.

Officers Wounded: CAPTAIN G.H. SAWYER, LIEUT G.E. HAWKINS, 2nd LIEUTS H.F.R. MERRICK, R. LEWIS, and G.W. LINDLEY. (The last two named were not admitted to hospital

Other Ranks: Killed 32, Missing 143, Wounded 216. For the report of the operation, see Appendix III, "Report by LIEUT-COLONEL G.P.S. HUNT, Commanding 2nd Royal Berkshire Regiment."

1 man admitted to hospital sick.

However, the detailed account in ‘Appendix III’ tells the story of the day as the battalion moved forward:

It was very dark at the time of the assault. In the deep and narrow trenches it was difficult to see what was happening and in the deep dugouts even more so. Some of the enemy fired from dugouts, but it does not seem they hit many men. Some were killed coming out. The men were little inclined to spare anyone and dugouts were cleared by bayonet, revolver or bombs; torches being used in some cases to discover whether they were occupied.

This sounds like success, but success was very limited; the battalion failed even to take all of the enemy first line and, by 1pm it was recognised that the attack had failed and the men withdrew to their own lines. For a full account of the 2nd Battalion’s action see the account here.

This was Albert’s first significant action, and his last; he died that day, though this was not clear at the time. Some men were known to have been captured leaving hope that any man missing from the roll-call after the action could be alive in enemy hands. In Albert’s case it was known that he had been wounded (probably reported by a comrade who saw him fall), but there would still be hope of his survival. Over the following months his family and friends would monitor Red Cross reports, hoping to hear he was a prisoner somewhere; every time a letter arrived they would hope it was addressed in his handwriting. Eventually the War Office accepted the lack of news of Albert meant that he was dead:

Newbury Weekly News, 21 Sep 1916 – Local War Notes

Private Albert Swain, of the Royal Berks, was reported wounded and missing at the battle of Loos. It is now officially intimated that he was killed on September 25th, 1915. He was the only son of Mrs Illsley, of Raymond’s cottages, Argyle-road, and was nearly 20 years of age.

As the newspaper report suggests, Albert’s mother, Ada, had remarried (to Frederick Illsley) in late 1914. Frederick’s brother, Albert, was another victim of the conflict.

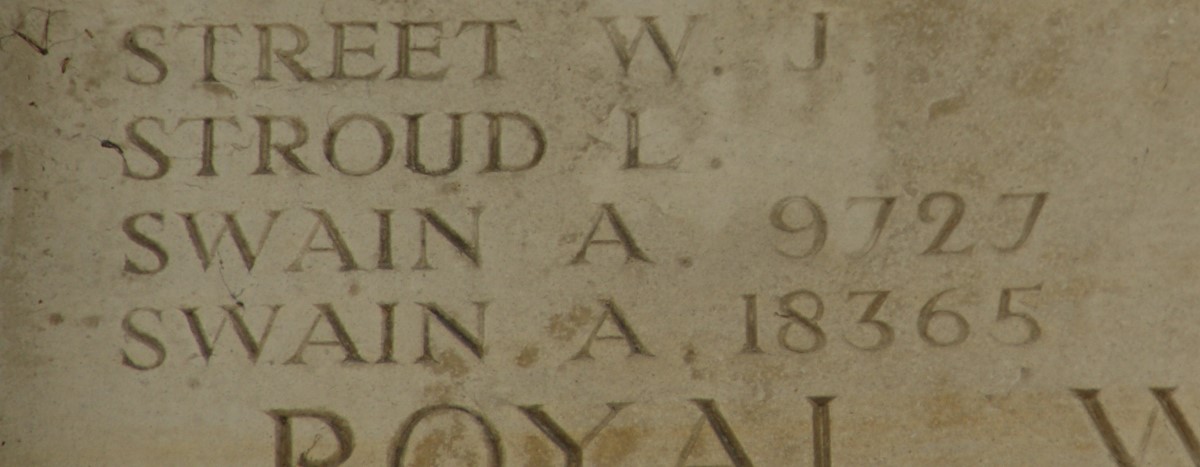

Albert's name (9727) on Ploegsteert Memorial. |

Albert’s body was never identified so his name is remembered on panel 8 of the Ploegsteert Memorial to the missing 6 miles north of Bois Grenier. Tthe name below Albert’s is another A Swain from the Royal Berkshire Regiment – Arthur Swain from Walsall, who died fighting alongside Albert at Bois Grenier. Their names are distinguished by the addition of their regimental numbers.

Abert's name on Newbury War Memorial. (uppr middle) |

Locally Albert is remembered on tablet 4 of the Newbury Town War Memorial and on the splendid Congregational Church Memorial , now located in Newbury Town Hall.

His name appears among a group at the bottom of the Congregational memorial; these were late additions to the memorial, added after it had been unveiled and dedicated on 18 July 1920.

Find a memorial :

| Died this day: | |

| 02 March 1943 | |

| K F Bartholomew | |

| Thatcham |

Like this site? Show your appreciation through a donation to a great charity.